US containerized imports stayed on an upward trend in 2016 despite strong headwinds that included excessive inventory levels, lower consumer spending, weak manufacturing activity, and Hanjin Shipping’s August collapse.

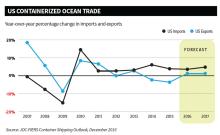

The US container trade in 2016 expanded an estimated 3.6 percent to a record of approximately 20.4 million twenty-foot-equivalent units on the back of subdued import prices and further gains in home sales. I expect further increases in imports in 2017 and a rise in exports for the first time in years.

Gains were seen across all sub-regional markets with the exception of Africa and Oceania. Northeast Asia contributed most to the import trade, adding 1.44 percentage points to growth, followed by Southeast Asia, which contributed 0.88 percentage points to growth. China again was the largest supplier of containerized goods to the United States — by far — accounting for 46.8 percent of the total US inbound trade.

That share was virtually unchanged from 2015, but down 1 percent from five years ago. This slight decline in China’s market share of US containerized imports may accelerate in the coming years as the incoming Trump administration begins to shape trade policy. There was no shortage of anti-China rhetoric during the campaign, with president-elect Donald Trump saying his administration would impose 35 percent tariffs on Chinese imports, while calling China an “unfair trader” and “currency manipulator.”

Chinese state media responded by raising the possibility of countermeasures that could include restrictions of sales of Apple iPhones in China, imports of US maize and soy, and outstanding orders from Boeing.

l

Although friction over trade and currency is likely to remain elevated in the next few years, an all-out trade war between China and the United States seems unlikely as both nations have a lot to lose. Retaliatory tariffs would be far more costly for China, in balance-of-trade terms alone. Nearly 17 percent of Chinese exports, a sum representing 4 percent of its GDP, went to the United States in 2014. In contrast, less than 8 percent of US exports, or less than 1 percent of its GDP, went to China.

In terms of containerized trade, however, the cost would be relatively equal. China shipped about 24 percent of its containerized exports measured in TEUs to the United States in 2015, and the United States shipped the same percentage of its exports to China.

The president-elect’s pledge to walk away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement in his first 100 days of office also imply grave ramifications. Ratification of the TPP would have given the United States five new free-trade partners — Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and New Zealand — and boosted the stubbornly weak growth in the trans-Pacific trade. The chances of the TPP passing now are slim.

On the other hand, a withdrawal from NAFTA would have adverse consequences for trade and economic growth for all three members, and possibly trigger a trade war in the worst-case scenario. US-Mexico trade volume has grown at a remarkable pace in recent years, clearly seen in the surface transportation market, but also in maritime trade data, although at a much smaller scale. US containerized imports from Mexico have more than doubled over the last five years, and totaled approximately 130,000 TEUs in 2016, according to data from IHS PIERS, a sister division of JOC within IHS Markit.

Looking into 2017, I anticipate US containerized imports to expand 4 to 5 percent, and reach a new peak of approximately 21.4 million TEUs, mainly on account of stronger economic growth even before any Trump fiscal stimulus. US real GDP is forecast to grow 2.3 percent this year after expanding by only 1.6 percent in 2016. Consumer spending growth is expected to moderate slightly over the next couple of years, although gains in real disposable income and jobs will continue to support it.

In the housing sector, meanwhile, we estimate existing home sales achieved measured progress in the fourth quarter of 2016 and should average above a 5.5 million-unit annual rate this year. Housing starts should average about a 1.2-million-unit annual rate this year and new home sales are forecast to grow to 670,000 for all of 2017, further supporting the inbound containerized trade. The major downside risk to the forecast centers around the possibility of growing protectionist populism in the United States and abroad that will challenge business confidence and global trade growth.

In the outbound trade, I estimate US containerized exports registered growth in 2016 for the first time in three years, around 1 percent. Gains were led by Southeast Asia, contributing 1.72 percentage points to growth in 2016 on the back of solid demand for aluminum blocks, soybeans, and fabrics, including raw cotton. On the downside, the east coast of South America registered sharp losses, accounting for a 0.50 percentage point subtraction from overall annual growth. US containerized exports to the east coast of South America have now fallen for five consecutive years, with Brazil as the main source of weakness.

Just when many emerging markets were recovering from sinking commodities prices, currencies, and stock markets over the past few years, the potential for rising protectionist populism and increases in US interest rates and the dollar are undesirable news. Any threatened protectionism (or withdrawing from free trade agreements, such as the TPP) would slow global trade growth even more and would hurt all emerging markets highly dependent on export trade. The Asian economies, which are among the world’s most dynamic traders, are especially vulnerable.

In Europe, the outlook is murkier because the outcome of the US election could embolden right-wing populist parties in Europe. It also could make the Brexit negotiations more complicated with European Union politicians taking a tougher stance to discourage European populists. The silver lining in this outlook for the eurozone is a weaker currency, which will help exports. Still, IHS Markit expects European growth to soften this year because of the increased political risks. In the eastbound trans-Atlantic trade, I anticipate US containerized exports to North Europe to pick up in a modest range of 1 to 2 percent, whereas exports to the Mediterranean region likely will register another year of volume losses, between 2 and 3 percent.

The Asia-Pacific region, on the other hand, continues to lead global growth, but uncertainty caused by global politics and slow progress on reforms means a return to stronger growth will take time. I anticipate the westbound trans-Pacific trade will expand less than 2 percent this year after growing approximately 4 percent in 2016.

Although the strength of the US dollar appeared to peak during the first quarter of 2016, subsequent international turmoil helped to prop up the greenback yet again. In inflation-adjusted terms, it now appears this strength may persist through 2017. In the IHS Markit forecast, a Federal Reserve interest rate hike in December, along with stronger domestic growth, helps drive the dollar higher through the first half of 2017. It then descends over several years, as growth rates and interest rates rise worldwide.

Until we get better indications of how much of the campaign rhetoric will translate into actual policy initiatives, I will remain cautious in my outlook for US containerized trade for this year and beyond. For 2017, I anticipate US exports again will expand at a modest pace, in the neighborhood of 1 percent, and total approximately 11.8 million TEUs, amid continued expansion in global economic growth. IHS Markit anticipates global growth, excluding NAFTA, to perform at a similar pace than in 2016, in the neighborhood of 2.5 percent.

The downside risks to the export forecast remain mostly geopolitical, but I’m also wary that the dollar will appreciate sharply until the beginning of 2018, and economic growth in major US export markets will come in lower than forecast on average, amid uncertainty related to Brexit and global political risks.

Mario O. Moreno is senior economist for IHS Maritime & Trade, the division of IHS Markit that includes The Journal of Commerce. Contact him at mario.moreno@ihsmarkit.com.